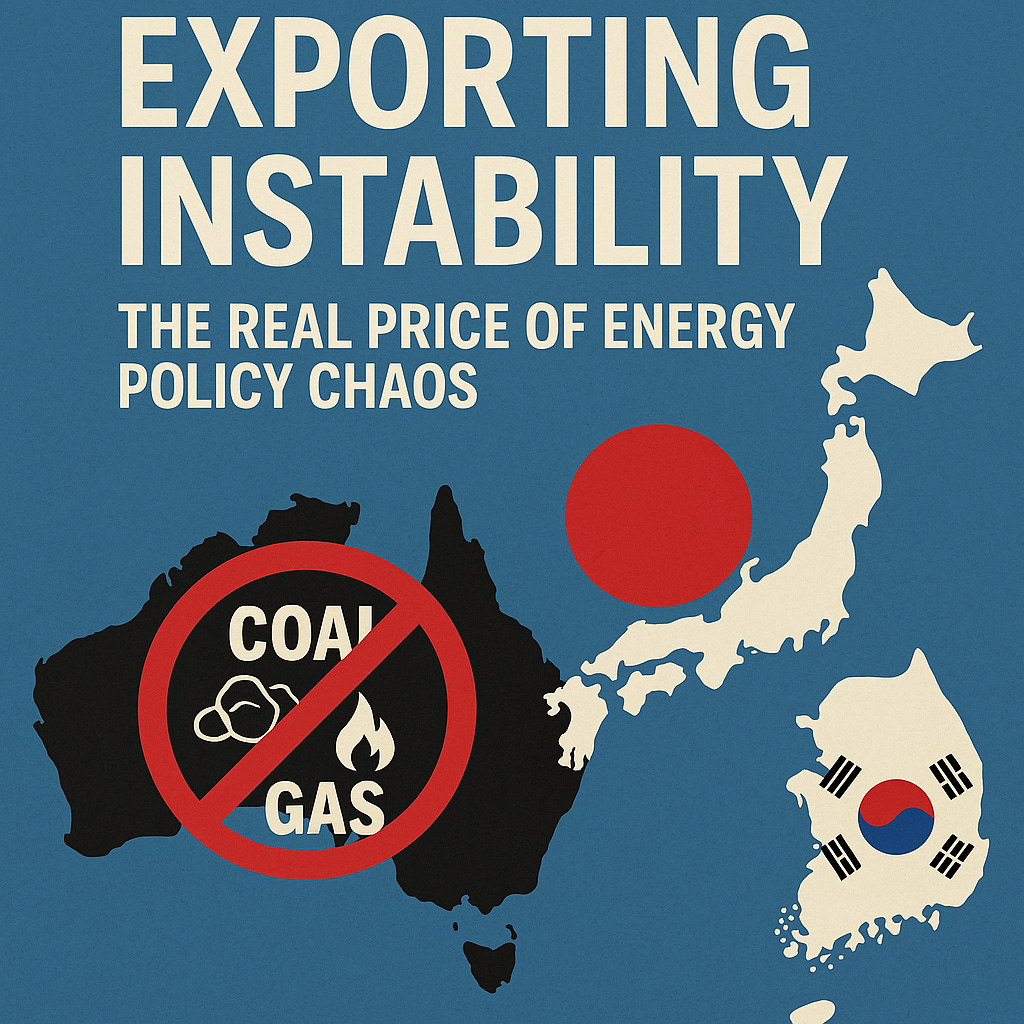

Exporting Instability

A former trade commissioner warns Australia is losing Japan and South Korea’s trust.

By Michael Newman

In 2024, Japan imported around $39 billion worth of Australian liquefied natural gas, accounting for about 40 percent of its total gas supply. More than 215,000 Australians are employed in the LNG industry, which remains a strategic, economic and geopolitical asset. However, the Albanese Government’s retrospective application of the Safeguard Mechanism — a policy that forces large industrial emitters to reduce or offset their emissions — along with other onerous regulatory hurdles, has created growing anxiety in Japan about the future reliability of Australian supply.

In March 2025, JERA’s LNG Senior Vice President Hitoshi Nishizawa lashed out at the Energy Exchange Forum in Western Australia, stating that unless progress was made on onerous Australian regulations, Japanese firms, including JERA (Japan’s largest power utility and gas buyer), would look elsewhere for LNG supply and future investment when their contracts expire in 2030.

The following month, Nikkei Asia reported:

“… a major energy deal involving U.S. liquefied natural gas [in Alaska] with the likes of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan was in the works, Trump administration officials said Tuesday, hinting this could lead to a possible reduction of tariffs...”

Japan has a massive automotive footprint in the United States, with Toyota, Honda, and Nissan holding a combined 30 percent market share. Despite significant local manufacturing, Japanese car imports now face 25 percent tariffs under U.S. trade policy. That may offer Tokyo a convenient pretext to shift focus away from Australia. With the U.S. accounting for 25 percent of global GDP and over a third of global consumption, pivoting trade toward America makes strategic sense — particularly given recent strains in the Australia–Japan relationship.

Even before the Trump tariffs, the alarm bells for Australia had been ringing for years. There seems to be a complacent misconception that Japan (and South Korea) need us more than we need them when it comes to resources. This attitude is not lost on our vital North Asian partners.

Comments such as those from Mr Nishizawa used to be the exception. Now they are becoming the norm. In my 42-year association with Japan, it is with a heavy heart that I hear the words “political risk” and “Australia” used in the same sentence, especially with respect to energy. They used to be mutually exclusive.

Japanese Ambassador to Australia, HE Kazuhiro Suzuki, said emphatically that his government and Japanese investors crave predictability in policy — something sorely lacking over the past three years. The Japanese do not need our grant or program funding. Policy uncertainty creates anxiety to commit capital. Taxpayers win twice if we can provide a consistent policy runway.

South Korean Ambassador to Australia, HE Seungseob Sim, reiterated similar sentiments. The Koreans have a strong desire to work with Australia. As sentimental people, they have not forgotten our commitment during the Korean War or the fact that Korea’s major steelmaker — POSCO — was built off the back of Australian iron ore after the company was laughed out of boardrooms in Brazil and the U.S. over five decades ago. They want to engage, but we are being unnecessarily difficult.

The cold hand of the bloated federal and state bureaucracies continues to provide out-of-touch advice to ministers — advice which has dire long-term consequences.

Some examples.

In 2021/22, KEPCO (Korea Electric Power Corporation), which supplies 85 percent of South Korea’s electricity, lost its High Court bid to develop the Bylong coal mine after a decade of delays and assurances it would be approved. POSCO, Korea’s major steelmaker, faced a similar setback when its Hume project in the NSW Southern Highlands — a proposed metallurgical coal mine — was blocked following local opposition. Together, the two companies lost A$1.2 billion, having trusted that Australia was acting in good faith. The fallout has echoed through industry bodies in Seoul, prompting renewed doubts about Australia’s reliability as a long-term investment partner.

In 2022, the Queensland Government under Annastacia Palaszczuk arbitrarily hiked coal royalties without consultation, raising the ire of Japanese Ambassador HE Shingo Yamagami. He publicly stated — uncharacteristically for a Japanese diplomat — that such action deeply disrespected the mutual relationship. So incensed by the lack of response from Palaszczuk, a year later Yamagami chose not to attend his own annual infrastructure conference in Sydney, instead flying to a minerals conference in Brisbane to berate the government.

The coal reservation policy introduced in NSW in February 2023 deepened already strained relations. It required producers to divert coal to domestic power stations, triggering alarm among Japanese and Korean companies concerned they would be unable to honour longstanding international contracts. NSW Treasury’s view — that North Asian firms were making bumper profits and could absorb the disruption — overlooked the reputational damage caused by breaching evergreen contracts. Although exemptions were eventually granted, the lack of prior consultation was troubling. After the state election, Treasurer Daniel Mookhey raised coal royalties. While he did engage in consultation and locked in the changes, it was more performance than partnership.

Meeting with Japan’s energy and resources security agency, JOGMEC (Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security), recently confirmed the difficulty of the present relationship — one that is now forcing them to seek alternatives. This is no longer a one-off theme. It is recurring.

Australia is in a precarious position. Over the past five decades, North Asian investors have paid tens of billions of dollars in taxes, employed hundreds of thousands of Australians, imported countless hundreds of billions in resources, and invested hundreds of billions more in our nation.

The Japanese and Koreans are committed to decarbonisation — but at a pace determined by sensible, rational economics. If Australia continues to prioritise climate zealotry over commercial realities, they will look elsewhere. We cannot expect them to dump coal and gas to fumble their way to net zero while crushing their industrial bases. They simply will not let that happen.

If state and federal governments continue to treat key trading partners with disdain, the next five decades may look decidedly different. It will be a spectacularly large own goal — one that could take decades to repair. And if that happens, we will have only ourselves to blame for our myopia.

Michael Newman has four decades of business experience in North Asia and served as NSW’s Senior Trade and Investment Commissioner to the region.

https://jp.linkedin.com/in/mike-newman-3896b810

They will buy from Alaska LnG instead/

https://open.substack.com/pub/themonentaryskeptic703/p/strategic-pincer?r=9wy0f&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

This is Bowen’s plan